Q: I’m curious about people who come to your live show and know you largely from these characters that you play on TV. I’d imagine that there are some surprises for them when they see you as the you-est you, right? You’re being yourself in these performances.

A: Most of my audience [knows] who I am and the ways in which I am different from Ron Swanson, for example. And if they don’t cotton to that, the differences are soon elucidated in my song, “I’m Not Ron Swanson.” There is a small percentage of the uninitiated who think that I’m gonna be a cigar-smoking shotgun enthusiast, so I usually have seven to 11 people leave in a huff muttering about what a snowflake I am.

I received a lot of new homophobic attention after my work in ‘The Last of Us.” So now I’ve written a song called “I Thought I Was a Man, But I Was Wrong.” I generally make hay out of the ways in which some of my audience has poor reading comprehension when it comes to understanding how actors work.

Q: Is there anything strange, challenging or exciting to you about being somebody who a lot of fans think of as a paragon of what is to be a man in this cultural moment where we’re all examining gender differently, and trying to have more expansive ideas about what that means?

A: It never occurred to me that I would be held up as some sort of ideal of masculinity, I suppose because despite the package that I was born in, and the voice that emanates from this beefy torso, I am me inside, and I’m a complicated, artistic, creative human being. I’m a giggly sap who also is good at chopping firewood and driving equipment and grilling red meat. That’s what I try to gently explain, to those sad Libertarian fans.

Even Ron Swanson — that’s why I said those fans have poor reading comprehension — he’s truly a very progressive and open Libertarian. He’s not right-wing, he’s not misogynist. He’s an incredible feminist, he’s a very gentle soul who just happens to have these old-fashioned, conservative ways of living.

I encourage my audience to squint their eyes and soften the boundaries between genders and between groups of people, and [let go of] the need to simplify and specialize human beings, and instead open the categories to where everyone is accepted with their own list of proclivities and attributes.

Q: Did you ever struggle with the dissonance between the way that your physical appearance made people think about you and the person that you actually wanted to be? Especially starting out as an actor where I feel like you’re constantly getting told, “Oh, you look like this type, you look like you should be this person.”

A: Absolutely. I think that is true for just about everybody, whether you struggle for a long time — which I did — to begin to get roles of any size, or if you’re the lead in the show right out of the gate. Everybody is being pigeonholed constantly, and not just as an actor. That’s one of the things that our society wants to do, is isolate us all.

When I first got to town, as a Chicago theater actor — I had done a handful of shows at Steppenwolf, for example — I was immediately categorized as a dramatic actor. And so I got to work on shows like “ER” and “The West Wing” and “Deadwood.” I actually had to get proactive in my 30s. I called Amy Poehler, who I’d known for a long time, and said, “How do I get people to see me as somebody who can make people laugh?” She had me come to the Upright Citizens Brigade in New York, where we were living at the time because Megan was working on Broadway, and I just started to do a couple of shows there. And suddenly the business was like, “Oh, I didn’t know you do comedy!” Then once I became known for “Parks and Recreation,” now people are surprised to see, “Oh, what are you doing in this dramatic role?”

Q: Take me back to that early time in your career. You leave Chicago, you go to L.A. As you say, you’re getting parts on these dramas. But as I understand it, there was also a period of time of auditioning and not getting stuff, right? You audition for Michael Scott in “The Office” and it goes to Steve Carrell. You have this time of having to stay in it, emotionally and mentally, during a period of your career where there were like more noes than yeses. What was that like for you?

A: You’re right. Things began to go well in Chicago, mainly in the theater, but I got a couple of small film jobs and got a SAG card, and that momentum took me to Los Angeles. And it was one of the most ignorant life moves I ever made. I didn’t do much research. I didn’t really know anyone in Los Angeles. I was not aware that it was not a theater town. I couldn’t have fathomed that the biggest collection of acting and writing talent in the country wouldn’t be at least as good a theater town as Chicago.

I was by myself. I basically spent three solid years drinking too much. The first year, I was a broke jerk paying my rent with my carpentry tools while just flailing, not only at finding remunerative work as an actor but also with comprehending fitting the strange animal of myself into the machinery of Hollywood. It was just a terrible cold-water plunge.

I began to get sporadic jobs. One big brass ring to actors starting out is what is called the top-of-show guest star. … It means you’ll get the top of the scale for the week’s paycheck, which at the time would be five or six grand, which would pay my rent for months. I would get one or two of those a year. When I got on “ER” in 1998, that was, for me, a six-month gold medal. Those are also signals, little breadcrumbs, left by the fates, by Lady Fortune, to say: “Keep finding this path. Keep looking for the tree blazes. Stick with it.”

It was a real crisis. … When things began to seem bleak, I was 29. I didn’t know if I had made the right choice and I didn’t know what to do. And I said, well, the thing that made me was working in theater, so even though it’s not a theater town, I just need to do a play. … Some friends hooked me up with an audition for a play, “The Berlin Circle,” by Charles Mee. And I ended up getting cast and the lead in this play was Megan Mullally, who had just had her first two seasons of “Will and Grace” and was about to win her first Emmy and become the international comedy legend that we all know her as. I fell in love and haven’t stopped smiling since. It will never be lost on me that I turned to my true vocation — even though it was illogical. … By listening to that voice, I met the love of my life.

Q: I was re-watching your episode of “The Last of Us” last night and I was wondering, when was the last time Bill played that piano? And of course, we as viewers don’t know if that’s in the script. But I’m curious if that’s something that you thought about. How much work do you do imagining things about the characters you play beyond what’s on the page?

A: That’s something I thought about a lot for that episode of “The Last of Us,” when it came to assessing: How should this sound? Should it sound ready for a concert? How often does Bill play? Has he ever played in front of someone else before?

The better the writing, I find, the less questions are required. Because, by definition, the thing that makes the writing good is that it’s already thought about so many of these questions, and so a lot of these nuances, I can find in the script. I can tell by the way Craig Mazin, who wrote it thoughtfully, has described for us this meal that the character Bill prepares for himself: He’s happy, he has a wonderful, rewarding life by himself. But then when he suddenly has company that he wants to invest in, [the script shows] how his cooking life changes, or not. How that comes to bear on his relationship with Frank. So there are all these little things. And we love to talk about them as we prepare to perform these scenes.

Q: Was there anything specific that you can remember about Bill that was not your idea but that came up during one of these conversations, whether it was with Craig or with other people in the cast?

A: Two things come to mind: One is a really fun conversation about what is going through Bill’s head when he finds Frank in his pit. Why doesn’t he just shoot him, first and foremost? And all of the tiny questions that had to be asked and answered in Bill’s psyche to get Frank to his dinner table, and then to get, ultimately, Frank into his heart. There is a lot of conversation there that I undoubtedly benefited from, from digging into the head of Craig, one of our most lauded screenwriters working.

The [other] is around the thought process that Bill went through on their last day, when Frank woke up and said: “Here’s what’s happening, here’s my last day, here’s what you’re going to do for me.” And how Bill romantically had the last laugh and said, “Guess what? I’m coming with you. I’m going to be your dreamboat until the last sip of wine.” Talking those out with Craig and Peter Hoar, our wonderful director, and [co-star] Murray Bartlett, those were some of the most exquisite episodes of table talk, really fleshing that out with my collaborators. All of the conversation gets unpacked, and then it has to be condensed back into the glass of wine in which Bill has, unbeknownst to Frank, packed a dose for himself. … Relishing that act, looking my life partner in the eyes, is one of the greatest, most joyful things I’ve ever gotten to perform.

Q: At the risk of undercutting such a beautiful experience for you, I think it’s very funny that there’s this parallel where you go from playing a guy on “The Last of Us” who thinks that the government is full of Nazis, to “Party Down,” where you are a man who is trying to make a government full of Nazis.

A: And Bill has a great line that he screams in the street about how the government are all Nazis! But you’ve done a great job of illuminating for my fans that are still in the dark about how acting works. … I can play Ron Swanson and turn around and play an aspiring white supremacist.

Q: You’ve named so many of these great writers that you’ve gotten to work with and whose work you seem to deeply appreciate. How are you feeling about the writers strike?

A: I’m infuriated. First and foremost, I’m commiserating with and supporting all my friends who are picketing in New York and L.A., and it makes me sad I can’t be there with them; I’m in Toronto working. But nonetheless the thing we keep saying to each other is: These fat corporate executives, who are selling a product — they are selling sandwiches, at great profits to themselves and their ilk, and denying any of those profits to the inventors of this sandwich. These people are serving Reubens and the actual creators of the Reuben are on strike.

The things that are being asked for, the stats that are being publicized, tell it so clearly, because of course they’re very well-written. The CEO of Disney last year made a quarter-billion dollars, which is the sum total of all they’re asking for all of the writers. That one salary would pay all of the requests. All they’re asking for is a wage and a promise that our stories will not be created by robots, which is very terrifying.

My analogy is not great. It’s not a sandwich. It’s the original creative stories by which we all are fed our souls. It’s the medicine for the souls of the world, and to behave in such an exploitive way — [they] might as well be running a mine for blood diamonds.

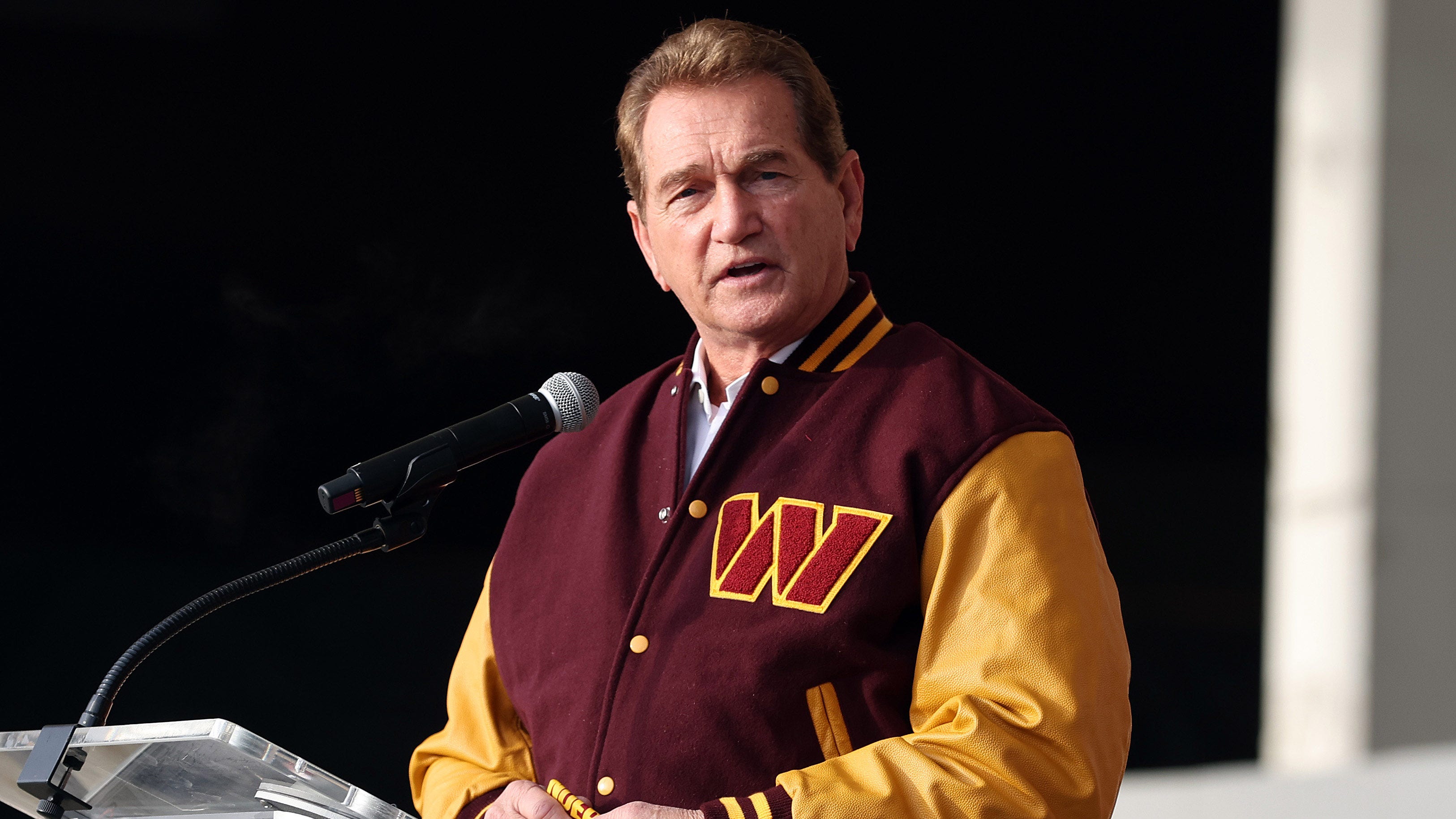

Nick Offerman performs at MGM National Harbor in Oxon Hill, Md., on May 26.