As COVID-19’s negative impacts on public health started to subside, the conflict in Ukraine and China’s strict “zero-COVID” limitations introduced more instability to international supply chains, sending inflation to four-decade highs in many economies, raising food prices, and fueling energy rates.

The world economy is in stormy waters heading into 2023 after a turbulent year.

On the plus side, China’s reopening following three years of stringent pandemic bans gives a confidence boost for the global recovery.

Following are the economic trends to analyse in 2023, according to Al Jazeera.

China’s reopening

China started the process of rolling back its divisive “zero-COVID” policy earlier this month as a result of rare large-scale demonstrations after nearly three years of severe lockdowns, mass testing, and border restrictions.

China’s international borders will reopen on January 8.

The resumption of the second-largest economy in the world, which has seen a sharp slowdown in recent months, should give the global recovery a fresh impetus.

Major exporters like Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore would benefit from an increase in Chinese consumer demand, and worldwide companies like Apple and Tesla who experienced recurrent disruptions under “zero-COVID” would also benefit from the lifting of restrictions.

At the same time, there are serious risks associated with China’s abrupt U-turn.

Beijing has stopped releasing COVID numbers, but hospitals all around China have reported being overrun with sick people, and mortuaries and crematoriums have reported being overrun with bodies.

According to some medical professionals, China could experience up to 2 million fatalities in the upcoming months.

Slowing growth and recession

In 2023, price growth is predicted to decelerate, but economic growth will also inevitably slow down significantly as interest rates rise.

The IMF predicts that after expanding by 3.2% in 2022, the global economy would only expand by 2.7% in 2023. The OECD predicted a less impressive performance this year, with a growth of 2.2% as opposed to 3.1% in 2022.

Many gloomy analysts anticipate a global recession in 2023, just three years after the pandemic-related slowdown.

The Economist’s editor-in-chief Zanny Minton Beddoes painted a bleak picture in a column last month, which was succinctly summarised by its title: “Why a worldwide recession is unavoidable in 2023.”

The IMF’s chief economist recently warned that 2023 may still feel like a recession for many people even if the world economy does not technically enter one.

Globalisation

The fight against globalisation intensified this year and is expected to pick up steam in 2023.

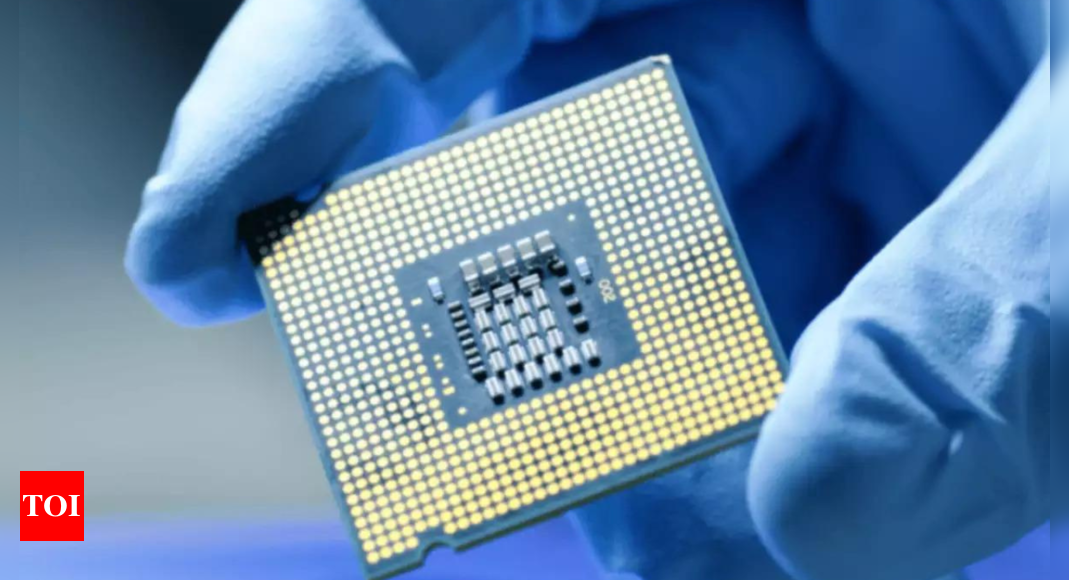

In an effort to hinder the growth of the Chinese semiconductor industry and promote self-sufficiency in chip manufacturing, US President Joe Biden signed the CHIPS and Science Act in August. This law prohibits the shipment of advanced chips and manufacturing equipment to China.

“The West, and particularly the US, are increasingly threatened by China’s economic trajectory and respond with economic and military pressure against the emerging superpower,” the founder of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s biggest chip manufacturer, said.

Bankruptcies

Bankruptcies actually decreased in several nations in 2020 and 2021 despite the economic havoc caused by COVID-19 and lockdowns because of a mix of out-of-court settlements with creditors and significant government support.

For instance, in the United States, 16,140 companies declared bankruptcy in 2021, compared to 22,910 in 2019, and 22,391 in 2020.

In 2023, this pattern is expected to change due to increased energy costs and interest rates. According to Allianz Trade, worldwide bankruptcies would increase by more than 19% in 2023, surpassing pre-pandemic levels.