While many universities are proud to talk about how they fight climate change, some also invest in and accept donations from the same oil companies that drive global warming. Experts and students are calling those schools hypocritical and are demanding change.

CBS News’ “On the Dot” environmental series investigates the scope of the problem, starting with the University of Texas System, which collected $2.2 billion in oil and gas royalties last year.

Drill ‘Em Horns

When it comes to sustainability, the UT Austin campus promotes itself as a leader among universities by reducing emissions and waste, conserving energy and water resources and building green buildings.

“I still want to give credit to the university for taking action on reducing emissions on campus. But that’s only a small part of the picture,” said Ella Hammersly, a student and climate activist at the university.

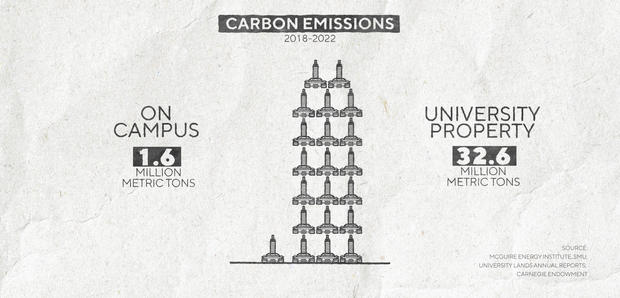

The bigger picture comes into focus hundreds of miles from the Austin campus, in the Permian Basin oil fields of West Texas, where 30% of the America’s oil is drilled. That’s where the UT System owns 3,000 square miles of property.

On the property energy companies lease land, extract oil and gas and pay royalties to the university system, which includes Austin and 12 other locations.

Oil revenue has helped make the University of Texas the richest public university system in America, with an endowment of $42.7 billion, according to a report by The National Association of College and University Business Officers. Number two is the Texas A&M System, with $18.2 billion, which also gets a cut of oil royalties from university properties in West Texas.

The scope of the emissions that come from burning the oil and gas drilled on university land has never been calculated before.

For this story, CBS News asked the McGuire Energy Institute at Southern Methodist University to run those numbers for the first time and found those emissions are 20 times higher than they are on campus.

“UT has a sustainability symposium every year. We have a sustainability master plan. All of these things are going on while at the same time billions of dollars are being invested into oil and gas,” Hammersly said.

Under Texas law, the money generated from oil and gas royalties is primarily used for campus construction projects across the state. Less than 1% goes toward financial aid.

UT student activist Anya Gandavadi says it’s time to update the law and its emphasis on oil profits.

“I think that investing in the future of the country, in the world, involves taking into account what science says, what people say, what communities say are hurting them and rewriting those laws,” she said.

For the world to limit the worst effects of climate change, nations will have to drastically reduce their carbon emissions. The International Energy Agency, a global group with a mandate of ensuring energy security, in 2021 called for an end to investment in new oil and rapid transition to renewable energy sources.

That’s not happening on university property in the West Texas oil fields where new lands are being leased and new wells are being drilled.

Dr. Michael Mann, climatologist at the University of Pennsylvania and a critic of the fossil fuel industry, is calling for change, even in Texas.

“What more influential message would it send if the flagship university of one of our most fossil fuel-driven states, Texas, were to take true leadership when it comes to the clean energy transition? It would impact the entire conversation here in the United States and around the world,” Mann said.

The University of Texas system declined to be interviewed for this story and provided this statement:

“The oil and gas production in the Permian Basin is responsible in large part for the United States’ remarkable energy independence, and it is a strategic national resource that would be tapped regardless of ownership.

Through ownership of the University Lands, beginning with the Texas Constitution of 1876, royalties received by the University of Texas System and the Texas A&M System have positively impacted millions of people who have benefitted from historic investments in financial aid, faculty support, teaching, research, medical buildings and more.”

While the university does lease some land for wind and solar farms, those projects account for 0.2% of its 2022 revenue from university property. Mann believes that the state of Texas, blessed with wind, sun and wealth, can and should lead on America’s energy transition.

“So that little sliver has to become the full thing. It has to become 100% and they need to move dramatically away from using that land to worsen the climate crisis, to using that land to make a profit in helping lead us down this path of clean energy,” he said.

University research and fossil fuel donations

A university doesn’t have to own its own oil fields to benefit from the fossil fuel money. Many schools, including Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, accept donations from oil and gas companies to support climate change research.

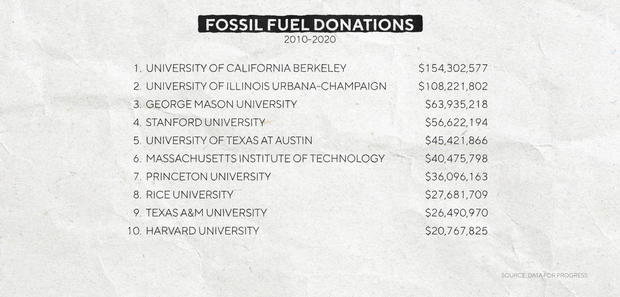

Between 2010 and 2020, Stanford accepted $56.6 million in donations from oil and gas companies, according to research by the progressive think tank Data for Progress. That puts Stanford in the Top 10 of universities accepting fossil fuel donations.

June Choi is a PhD student who came to Stanford to study at the new, $1.7 billion Doerr School of Sustainability. She was angry to learn the school would accept funding from fossil fuel industry partners.

“A total contradiction,” she called it.

In response, Choi and other students and faculty created a group called the Coalition for a True School of Sustainability and protested last year’s ribbon-cutting celebration at Stanford’s Doerr School.

“We were kind of crashing the party, really. And there was just so much energy. So, it created a lot of excitement,” she said.

Mann, at Penn, says when universities accept fossil fuel company donations for climate change research, it can cast a positive light on the very industry that’s at the root of the problem.

“[The fossil fuel companies] are purchasing the name Stanford University, and that is worth a lot to a fossil fuel industry that’s trying to purchase credibility. ‘Hey look, we’re trying to solve the problem and we’re working with the greatest universities around to do so,'” he said.

Philippe Roberge

What the Stanford activists want is a university ban on those donations, like the policy Princeton University in New Jersey was the first and only university to implement in 2022. Princeton created a list of 90 fossil fuel companies from which it will not accept donations.

In a process called dissociation, Princeton targeted companies involved in the “most-polluting segments of the industry” and a history of spreading “corporate disinformation” about climate change.

The biggest corporation on the list is ExxonMobil, which says it had donated $12 million to Princeton. In a statement to CBS, ExxonMobil wrote: “Close collaboration between industry and academia is essential to finding practical solutions to climate change.”

Princeton’s policy allows for companies to re-associate with the university in the future if they can meet the school’s criteria.

“And that’s great because then the university is really in a position to say, look like we are really constructively engaging with these companies and contributing to shifting the needle on their actions, Choi said.

The work of student organizers at Stanford is beginning to pay off. The university, which declined to be interviewed for this story, recently formed a committee to “review fossil fuel funding of research.”

“It’s a very positive sign, because that is exactly the beginning of a transparent process that we’ve been asking for,” Choi added.

Exiting fossil fuel investments

Many large institutional investors, including universities, buy stock in fossil fuel companies. In a nationwide movement, 50 universities or university systems have exited those investments. It’s a process called divestment.

Rutgers University is the largest state university system in New Jersey. After years of pressure from students and faculty, Rutgers announced in 2021 that it would permanently sell off those investments.

“I think you’re seeing increasingly universities becoming uncomfortable trying to pursue revenue streams in these industries that they know are punishing the earth,” Rutgers President Jonathan Holloway said.

According the Global Fossil Fuel Divestment Commitments Database, of the 10 largest endowments in the America:

-

Six universities have fully exited their investments: Harvard University, Yale University, Stanford University, Princeton University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of Michigan.

-

One has partially exited: University of Pennsylvania.

-

Three maintain their fossil fuel investments: Notre Dame University, University of Texas and Texas A&M University.

At Rutgers, a committee of faculty, students and staff helped create a divestment policy that put an end to all investments in fossil fuels, moved those investments to environmentally friendly index funds which actively seek investments in renewable energy.

“If we don’t do this work for the future that we’re not going to see, the one thing we know is the future will be worse. We know that. So, if we know that, don’t we have an obligation to do something about it? I think we do,” Holloway said.