In the other, Mr. Denneny was a feisty linchpin of the gay literary scene. He nurtured up-and-coming talent while working as an editor of Christopher Street magazine, which he co-founded in 1976 and promoted as a gay version of the New Yorker, and at St. Martin’s ran Stonewall Inn Editions, which he launched in 1987 as the first gay imprint at a major publishing house.

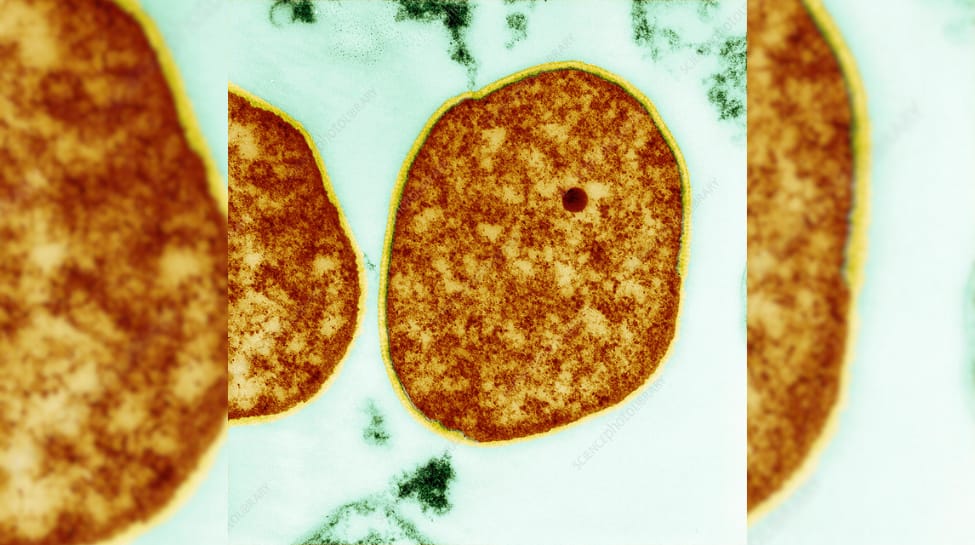

Mr. Denneny, who sought “to normalize the publishing of gay books,” released canonical titles by Allen Barnett, David Carter, Larry Kramer, Paul Monette, Edmund White and the journalist Randy Shilts, including “And the Band Played On,” Shilts’s best-selling 1987 chronicle of the AIDS epidemic.

In the book’s acknowledgments, Shilts wrote that his “reporting would never have been transformed into a book if it were not for the faith of” Mr. Denneny, who “believed in this project when most in publishing doubted that the epidemic would ever prove serious enough to warrant a major book.”

Mr. Denneny, who was often described as the first openly gay editor at a major publishing house, was 80 when he was found dead April 15 at his home in Manhattan. He was believed to have died about three days earlier of “a cardiac event, likely a heart attack,” said his brother Joe Denneny.

He died weeks after the publication of his book “On Christopher Street,” which explored the gay community’s evolution since the 1969 Stonewall uprising and featured some of his earlier writing.

“It’s probably too much to say that without Michael there would be no gay literature,” said Keith Kahla, an executive editor at St. Martin’s and a former assistant to Mr. Denneny, “but it would be a very different landscape, because once he started to publish and show it was possible to write about these lives, writers and other editors were inspired and emboldened.”

When Mr. Denneny created Stonewall Inn Editions, there were only a few independent gay and lesbian publishing companies, including Alyson Books in Boston. His imprint helped bring gay books to a mass audience while offering a sense of coherence and permanence for its titles, beginning with “Buddies” by Ethan Mordden, “Joseph and the Old Man” by Christopher Davis, “Blackbird” by Larry Duplechan and “Gay Priest” by the Episcopal minister Malcolm Boyd.

Through the imprint and St. Martin’s as a whole, Mr. Denneny went on to champion the work of gay writers chronicling the AIDS epidemic, whether through works of poetry, fiction or investigative journalism. He published one of the earliest books on the disease — “The AIDS Epidemic” (1983), edited by Kevin Cahill — and signed up dozens more, with the New York Times reporting in 1987 that he “may have published more books on AIDS than any other editor at a commercial house.”

A number of those works were by friends of Mr. Denneny’s who died of complications of AIDS, including Barnett, who died at 36; Monette, at 49; John Preston, at 48; and Shilts, at 42. Such writers “became our first responders,” the veteran editor Ira Silverberg wrote on Instagram after Mr. Denneny’s death. “They captured pain, lust, fear, empathy, and rage for us. Some of us were so numb and traumatized that we couldn’t access our own.”

While Mr. Denneny edited gay writers for virtually his entire career, he also was known for supporting authors across the literary spectrum. He collaborated with the essayist Renata Adler and the memoirist Lars Eighner, edited autobiographies by the Watergate conspirator G. Gordon Liddy and the action star Mr. T, and worked on award-winning mystery novels by Linda Barnes and Eliot Pattison.

Many of his first-time writers, including Thurman, were young and relatively untested. In a phone interview, she said that Mr. Denneny contacted her after reading a Ms. magazine article she wrote about Dinesen and suggested that she write a full-length biography of the renowned Danish author, whose real name was Karen Blixen.

“I said, ‘You’re out of your mind, I’ve never written anything longer than 10 pages.’ And in the course of a few conversations, he talked me into it,” Thurman recalled. “His confidence in me was the only thing that gave me any hope that I could actually do it. It took seven years.”

Her Dinesen book, subtitled “The Life of a Storyteller,” received a National Book Award and partly inspired the 1985 movie “Out of Africa,” with Robert Redford and Meryl Streep. It also led to a long friendship with Mr. Denneny, who once enlisted her to serve as an interpreter for the French philosopher Michel Foucault while showing him around “the Piers,” the gay cruising scene on the Greenwich Village waterfront.

“He was a gay Virgil,” she said of Mr. Denneny. “He took people through hell, back up through purgatory to paradise. As an editor, that’s how I would characterize him. He was very attuned to the poetry of this world.”

The oldest of three sons, Michael Leo Denneny was born in Providence, R.I., on March 2, 1943. He grew up in nearby Pawtucket, where his mother was a mill worker and his father handled mail. “It could be so gloomy at times that Michael got seriously into reading,” said his brother Joe, Mr. Denneny’s only immediate survivor.

Mr. Denneny graduated from the University of Chicago in 1964 with a bachelor’s degree in history. He stayed on to do graduate work with the school’s Committee on Social Thought, where he studied under the philosopher Hannah Arendt and received a master’s degree in 1970.

A self-described “hippie intellectual,” he protested the Vietnam War, worked part-time at the University of Chicago Press and increasingly identified as gay in the years after Stonewall. “Most people just thought it was my latest political enthusiasm,” he recalled in a 1996 interview. “So, in essence, I moved to N.Y.C. to try out being gay. It worked!”

Soon after he arrived in the city, in 1971, he was hired as an editor at Macmillan. He went on to work with writers including Shange, who encouraged him to publish more books by gay authors, but he found that he was a poor fit at the firm at a time when “everyone wore suits, white shirts and ties and had two martinis at lunch.”

In a 2014 interview with the LGBTQ organization Lambda Literary, he said that he was briefly fired after the company’s chief executive discovered that he was publishing his first gay book, “The Homosexuals” (1977) by Alan Ebert, which featured interviews with 17 gay men. Mr. Denneny said he was rehired after “every other editor, right up to the editor in chief, refused to present the book” at a sales conference, and after the legal department explained to executives that they were still obliged to publish the title.

Mr. Denneny was fired again, this time permanently, after he helped start Christopher Street, one of the first gay literary magazines, with friends including Charles Ortleb. The monthly magazine had a small but devoted audience and lasted some two decades, with contributions from writers and artists including White, Ned Rorem and George Stambolian.

For a time, Mr. Denneny worked at the magazine and at another gay publication, the New York Native, while also holding down his day job at St. Martin’s, which he joined in 1977. He also found time to write two books of his own, “Lovers” (1979) and “Decent Passions” (1984), drawn from interviews he conducted on intimacy and gay life.

Aside from two years at Crown, where he worked as a senior editor, Mr. Denneny remained at St. Martin’s until 2002, when he left to become a freelance editor and literary consultant. He was still trying to sharpen manuscripts, and he still believed — as he had decades earlier — that literature and politics were deeply intertwined.

“I was never worried about educating straight people,” he told New York’s Gay City News in 2004, looking back on his literary work in the years after Stonewall. “All of us were self-hating. We needed to reformulate gay imaginations, reimagine sex and relationships.

“The way you do that,” he continued, “is with books.”