This adaptation of Laurence Leamer’s “Capote’s Women: A True Story of Love, Betrayal, and a Swan Song for an Era” revels in those secrets even as it documents the tragic fallout. The title sequence is a cheeky delight, and the cinematography echoes Capote’s obsession with the perfect surfaces the swans create, lingering not just on flower arrangements, place settings and other exquisite details, but also on how miraculously unsoiled all that beauty remains by the swans’ misery, loneliness and bad marriages. Written by Jon Robin Baitz and directed by Gus Van Sant, Max Winkler and Jennifer Lynch, the show endorses Capote’s view of cosmetic perfectionism as a talent and a tragedy. The camera frames him aesthetically as the outsider he thematically is: Fashionably dressed but past his prime, struggling with writer’s block, he earns his place in these circles with juicy gossip and a cheeky but slightly servile approximation of friendship.

The show’s take on the other people involved is murkier. The swans — a bevy including Diane Lane as Slim Keith; Calista Flockhart as Jackie Kennedy’s sister Lee Radziwill; Chloë Sevigny as C.Z. Guest; and Naomi Watts as Babe Paley, the picture-perfect wife of CBS President William Paley — are impressive but mostly depthless. A coarse study of people obsessed with refinement, it sometimes resembles “La Côte Basque, 1965,” the brutally colorful Esquire piece that triggers the show’s events.

Whereas that infamous short story was a targeted and even malicious attack on some of New York society’s most carefully curated personal brands, the series remains more agnostic than judgmental. Most of the parties concerned behave badly and even vindictively at times, but the show rarely takes a position on who’s right or wrong.

If it sometimes seems as if “Swans” has no fixed perspective on the events it describes, it might be just as accurate to say it politely reproduces Capote’s contradictory feelings for his friends. The author’s admiration for Babe’s perfection (which Watts more than lives up to) is vividly represented and coexists with a subtextual loathing for the elite circles that rejected his mother, who in turn rejected him. Tom Hollander produces a marvelous and mercurial Capote, whom we believe when he rhapsodizes about Babe’s intelligence at one moment. We also believe him when he dismisses her as incurious and “easily bored” in the next. He judges her for what she sacrifices to produce the effect she does (such as being a good mother) and also loathes other women for failing to meet the standards she set. And so on.

Slightly hampering the series is that this isn’t an especially generative tension. Most of us are familiar with the feeling of loving (or being impressed by) aspects of the rich and famous and hating others, sometimes in the very same moment and for the same reasons. This Capote is, that is to say, more petty and relatable than exceptional. Or great. His misbehavior is lightly psychologized but not justified; the show portrays him at his most charming and socially savvy and observant and kind — but also as intentionally manipulative and cruel.

Any sympathy we feel for Capote (and I felt plenty) comes with a full and rather damning account of his shortcomings, addictions and flaws. That should heighten the drama at the show’s center. Will the “swans” forgive him? Should they? But this subplot stutters for a few reasons. One is the smallness of the swans’ world; we encounter them mostly in the fashionable restaurant where they have their anti-Capote conclaves, which makes it hard to gauge the extent of their celebrity or how much social fallout they suffered from the Esquire story. Another is that their disagreements are not — in the end — especially interesting. The third reason is simple geography: As Capote wanders away from New York City and succumbs to addiction, the show persistently circles themes of friendship, betrayal, regret and forgiveness, but in much the way water circles a drain.

Relieved though I am that “Swans” steers clear of postmortem hagiography, this excavation into how some gossipy friends turned on each other is juicy but a tad forgettable — which is, perhaps, exactly what gossip should be. The show sometimes starts to feel more like a broadside against the delicate and corrupting work of maintaining social relationships than (for instance) a clash between a conflicted truth-teller trying to expose the American elite and the lonely rich women he loves who guard its gates. The few defenses Capote ventures for his conduct are moving precisely because they’re so underthought and inadequate. The explanations are coverups for an impulsivity he can’t quite account for. Perhaps, beneath it all, the Esquire piece was a “love test” he deployed, in a self-destructive phase, to check whether the people whose rejection he feared most would finally follow through. Or love him anyway.

But Capote’s critique of the upper crust, specifically, gets mostly buried. Not even an intervention by James Baldwin (played by Chris Chalk) can nudge Capote, or the series, into channeling all that gossip into some bigger aim. Or claim.

That would be perfectly fine if it didn’t undercut the show’s other big question: What happened to the manuscript for “Answered Prayers,” the magnum opus that Capote was writing (or failing to write) when he died? The book from which “La Côte Basque” came was one inflammatory, fascinating excerpt? The show wants us to wonder about (and lament) the absence of a great thinker’s greatest work. As much as I enjoyed watching, I can’t say that — with this version of Capote, anyway — I did.

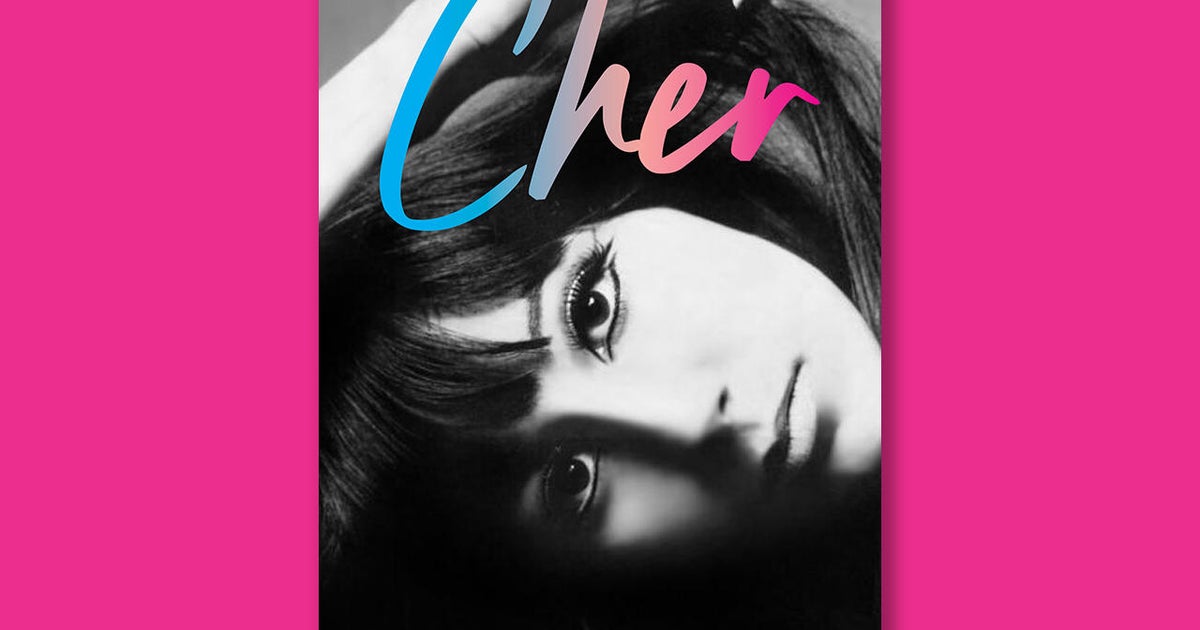

Feud: Capote vs. the Swans (eight episodes) premieres Jan. 31 with two episodes on FX and FXX, and will be available for streaming the next day on Hulu, with subsequent episodes airing weekly.