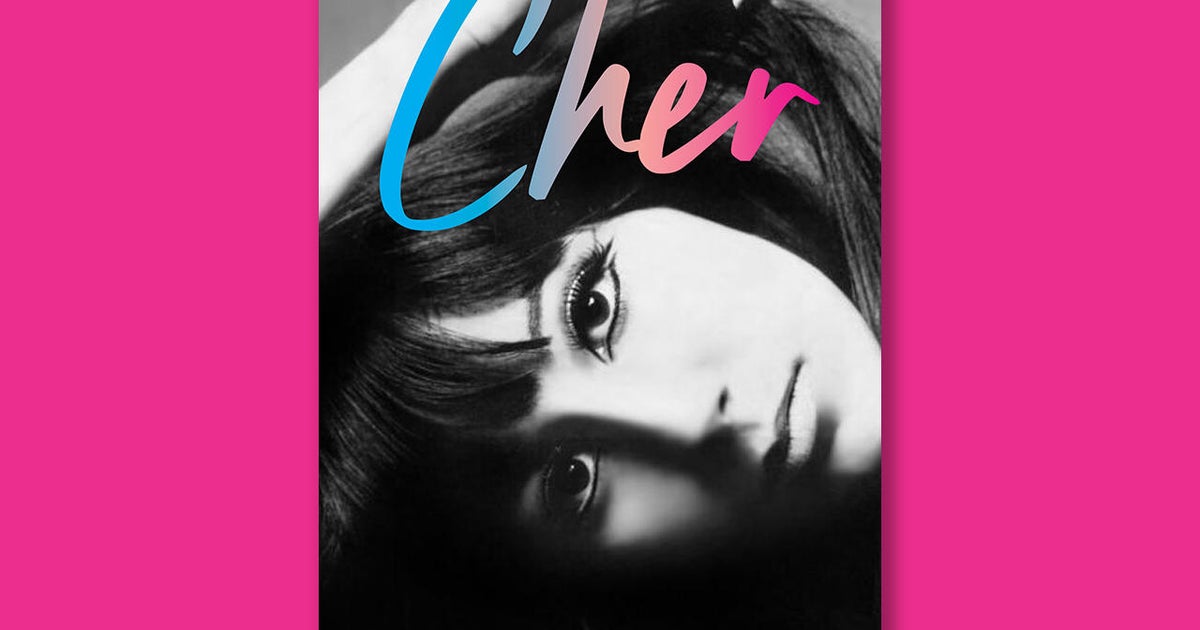

What’s so puzzle-dreamy about that? Maybe it’s the fact that greatness is automatically mysterious, and in terms of craft, this album comes remarkably close to eclipsing her 2019 mind-wiper, “Norman F—ing Rockwell!” Or maybe it has more to do with Lana’s use of convention to smash conventionality. For years, she has been jacuzzi-soaking her ballads in pop-rock Americana and Hollywood lore, crowding her lyric sheet with references and interpolations, casual nods and heady genuflections to the coolest songs ever written. But now, instead of landing like end-of-history collages or pat Warholian echoes, Lana’s songs simply describe a world where music exists. She was doing something, and a very famous melody happened to be floating by, then she wrote a new song about that moment.

Which means she lives inside the reality we all share, but she only makes music inside her own — so the more real everything gets in her songs, the less real it feels inside our heads. That’s no magic trick. When you’re a pop singer doing it at the very highest of levels, realism gets deeply weird.

Entirely at its own pace, this album gets weirdly sweet, weirdly sour, weirdly beautiful, weirdly harrowing. Lana raises the curtain with “The Grants,” a memorial ballad about a family (hers) who likes to sing John Denver songs (“Rocky Mountain High”), but despite the gospel choir she hired to join in, there’s a certain chill pushing against the song’s implicit warmth, as if death is near. A few tracks later, during “Candy Necklace,” she persuades the exuberant jazz pianist Jon Batiste to play a totally depleted melody, then moves her words toward the darkest edge, siphoning an existential crisis into lovers’ chitchat: “Sitting on the sofa, feeling super suicidal/Hate to say the word, but baby, hand on the Bible, I do.”

These aeriform songs rarely involve drums, which makes them feel timeless, at least in the short term. Listening to Lana sing for a few moments can feel like hours, which is probably the highest praise anyone’s distracted brain tissue can heap upon a singer in too-fast times. Something about the patience in her phrasing and the delicacy of her sibilation always turns the clock into vapor. Whether that’s on purpose, who knows? “Ask me why, why, why I’m like this,” she sings on the sprawling odyssey track “A&W,” perhaps suggesting that art is better formed by intuition than intention. “Maybe I’m just kind of like this.”

Some of the lyrics on this album are so good, they almost don’t need to be sung. Here she is on “Fingertips,” trying to take a step back from contemplating motherhood and the inevitability of death: “It wasn’t my idea, the cocktail of things that twists neurons inside.” Here she is on “Fishtail,” whisper-singing a metaphysical compliment so hot, it probably flattered its recipient into oblivion: “You’re so funny, I wish I could skinny-dip inside your mind.”

As for the most off-putting words on the album, they appear early in the proceedings, and on someone else’s lips. “Judah Smith Interlude” is a some four-minute sermon excerpt from a celebrity megachurch figure who’s on the record calling homosexuality a sin. Smith shouts some insipid, cool-preacher mush about resisting lust and temptation while the woman recording it (presumably Lana, presumably on her phone), giggles at a few lines and says “yeah” in a tone that makes it impossible to tell whether she’s smirking or nodding along.

Why include this? Is it some “There Will Be Blood”-ied meta-comment on God and capitalism in America? Or is this just something that happened in Lana Del Rey’s weird reality on some dim Sunday morning in California, and now here it is in our lives, too? Maybe there’s no deep intention here, just intuition. Maybe life is just kind of like this.