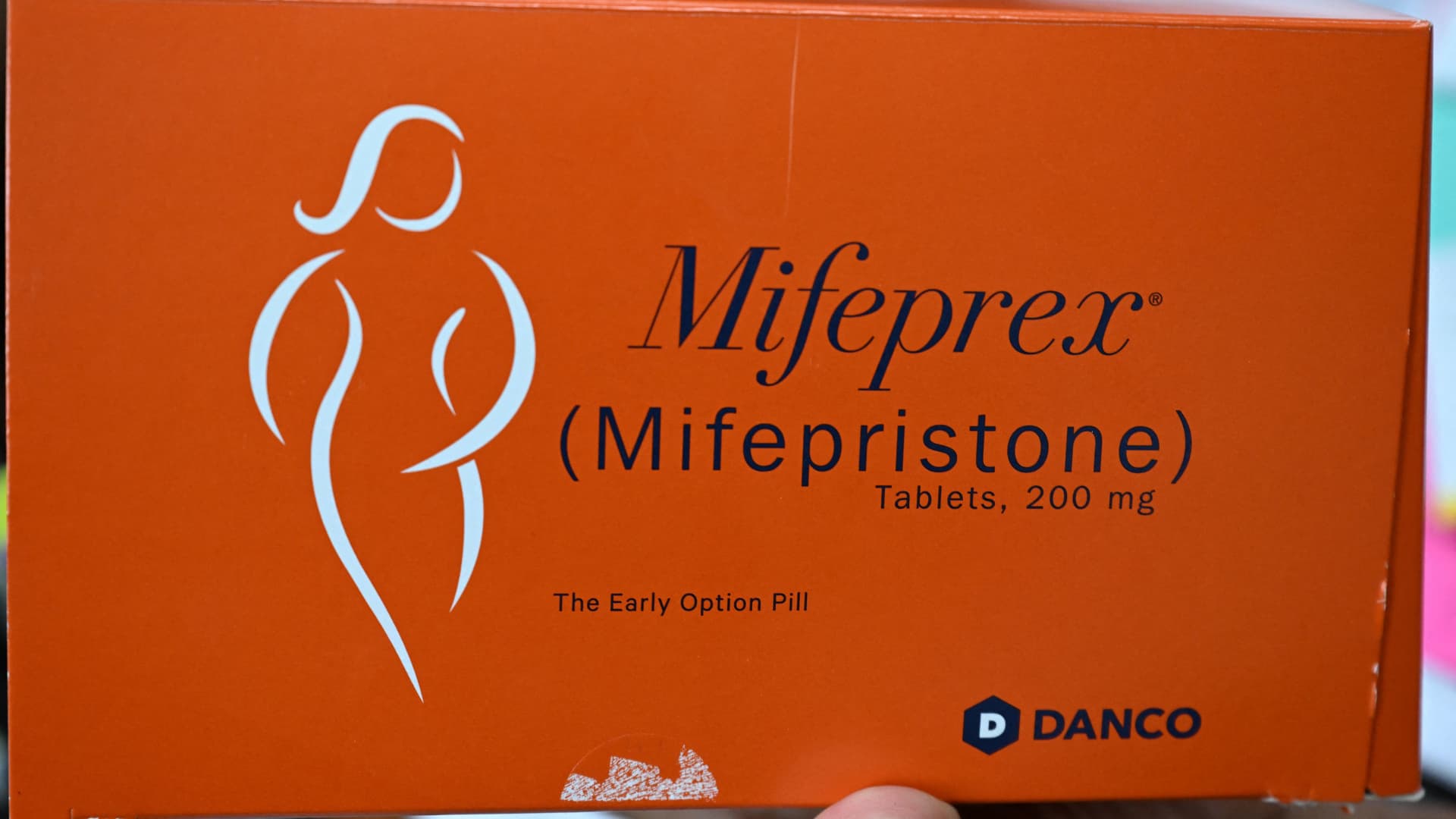

A federal judge in Texas may try to invoke an obscure 19th-century law called the Comstock Act to roll back mail delivery of the abortion pill mifepristone.

Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk of the U.S. Northern District of Texas heard oral arguments Wednesday in a closely watched case in which medical associations who oppose abortion are challenging the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of mifepristone. At the hearing’s conclusion, Kacsmaryk said the court will issue an order and opinion “as soon as possible.”

The central aim of the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, the antiabortion group that filed the lawsuit, is to pull mifepristone from the U.S. market. But Kacsmaryk could stop short of blocking sales and instead order the FDA to impose tougher restrictions on how the pill is distributed, legal experts said.

His rationale could hinge in part on the Comstock Act. He raised the 1873 law repeatedly during last week’s hearing, and appeared more sympathetic to the arguments laid out by the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine’s attorneys than those presented by the government’s lawyers.

The anti-abortion group’s attorneys argued that the Comstock Act and other laws ban mail delivery of mifepristone. They claimed the FDA’s 2021 decision to allow patients to receive the pill by mail was illegal as a consequence. Erik Baptist, an attorney representing the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, said any ruling against the FDA should be “universal and nationwide.”

The Biden administration is expected to swiftly appeal any ruling against the FDA. During last week’s hearing, Justice Department lawyer Daniel Schwei asked the judge to pause any order against the FDA pending the government’s appeal or impose an administrative stay of at least 21 days.

The Comstock Act has not been enforced in decades, said Rachel Rebouche, an expert on reproductive health law at Temple University. But Kacsmaryk could try to “breathe life into the Comstock Act” through a ruling that blocks the FDA’s move to drop an in-person dispensing requirement and allow mail delivery of mifepristone, Rebouche said. Rebouche was one of 19 drug law experts who signed a brief to the court in support of the FDA.

Congress passed the Comstock Act in 1873 after an anti-vice crusader named Anthony Comstock successfully lobbied lawmakers to declare “obscene” materials as not mailable. This included every substance, drug or medicine advertised for use in abortions.

Join CNBC’s Healthy Returns on March 29, where we’ll convene a virtual gathering of CEOs, scientists, investors and innovators in the health-care space to reflect on the progress made today to reinvent the future of medicine. Plus, we’ll have an exclusive rundown of the best investment opportunities in biopharma, health tech and managed care. Learn more and register today: http://bit.ly/3DUNbRo

These provisions in the Comstock Act largely went unenforced after the Supreme Court established federal abortion rights in Roe v. Wade. But Republican politicians and organizations that oppose abortion have sought to invoke the 150-year-old law after the Supreme Court reversed Roe last year, as they try to stop the proliferation of mifepristone.

“Pills in the mail are hard to track down, they more easily circumvent states’ abortion bans,” said Rebouche. “You can order them from abroad, you can walk across the border, there’s any number of ways to mail medication abortion pills. This is an existential crisis for the antiabortion movement.”

At least 12 states have banned abortion since Roe fell, and several states still require patients to obtain mifepristone in person. In February, 21 Republican attorneys general warned Walgreens and CVS against mailing mifepristone in their states.

The Justice Department, in a legal opinion in December, said the Comstock Act does not ban mail delivery of mifepristone when the sender does not intend for the recipient to use the pill unlawfully. The opinion cited multiple federal court rulings dating as far back as 1915 that narrowed the scope of the Comstock Act’s provisions on abortion.

But Kacsmaryk pressed government lawyers on what he should make of the Justice Department opinion compared to the “fairly definitive reading” of the Comstock Act’s language.

The judge appeared sympathetic to 22 Republican attorneys general who filed a brief to the court arguing that the FDA’s actions on mifepristone violate the Comstock Act. He raised multiple times the argument of the GOP attorneys general that the FDA is undermining the states’ ability to regulate abortion.

Kacsmaryk did not mention a brief filed by 22 Democratic attorneys general, who said a ruling against the FDA would jeopardize abortion access in their states where the procedure is legal.

Kacsmaryk seemed to suggest that FDA actions on mifepristone had “changed the field of federal-state relations vis-a-vis regulation of abortion.” He asked an attorney for the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, Erin Hawley, to weigh in on the arguments of the Republican attorneys general.

Hawley told the judge that if the Justice Department opinion on the Comstock Act is correct, “you are really seeing a sea change in federal-state relations.”

“The Dobbs decision said that it left to the people, the elected representatives, the power to protect life,” Hawley told the judge. She described the Justice Department opinion as an “affront” to the states because it denies them the power to set health policy within their boundaries.

Kacsmaryk later asked Justice Department attorney Julie Straus Harris what importance the government gives to the arguments of the Republican attorneys general in their brief to the court.

Harris said the FDA’s determination that mifepristone is safe and effective does not impose any obligation on the states or their residents. Rather, the antiabortion groups who filed the lawsuit are seeking to dictate an abortion policy that would affect people nationwide, she argued.

“But the plaintiffs are the ones here who are trying to dictate national policy by asking this court to withdraw the agency’s determination as to safety and effectiveness,” Harris told the judge.

The Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine has asked the judge to set aside every major regulatory action the FDA has taken on mifepristone, including its approval in 2000. The group is targeting the FDA’s 2021 decision to allow mail delivery of the pill, as well as a 2016 decision to reduce doctor’s visits and the 2019 approval of a generic version of mifepristone.