Social Affairs Correspondent

BBC

BBCBy the entrance to Furness General Hospital in Barrow-in-Furness sits a sculpture of a moon with 11 stars. It is a memorial to the mother and babies who died unnecessarily due to poor care at the hospital between 2004 and 2013.

Inscribed underneath is a short verse: “Forever in our hearts; Forever held in the love that brought you here; Our star in the night sky, spring blossom, summer rose, falling leaf, winter frost; Forever in our hearts.”

When the memorial was unveiled in 2019, Aaron Cummins who is chief executive at University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Trust, which runs the hospital, said: “We will never forget what happened. We owe it to those who died to continually improve in everything that we do.”

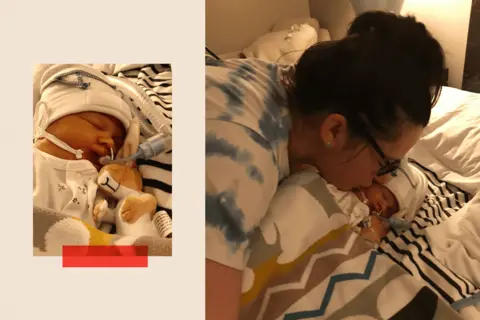

Barely a month later, Sarah Robinson stepped into a birthing pool at the Royal Lancaster Infirmary, a hospital run by the same NHS trust. She was about to give birth to her second child.

Within an hour, Ida Lock was born; within a week, she was dead.

PA Media

PA MediaWhat her parents were put through on that day – and in the years since – goes a long way to explaining why maternity services in England have failed so many families.

The inquest into Ida Lock’s death, which concluded last week, exposed over five weeks why maternity services across England have long struggled to improve – and this one case holds a mirror to issues that appear to be prevalent across a number of trusts.

‘I thought I’d done something wrong’

The memorial the trust erected at Furness General Hospital followed a damning inquiry into the trust’s maternity services.

That investigation, carried out by Dr Bill Kirkup and published in March 2015, found there had been a dysfunctional culture at Furness General, substandard clinical skills, poor risk assessments and a grossly deficient response to adverse incidents with a repeated failure to properly investigate cases and learn lessons.

Morecambe Bay became a byword for poor maternity care and the trust promised to enact all 18 recommendations from the Kirkup review. And yet that never happened.

“We wouldn’t be in this situation now if they’d followed those recommendations,” says Ms Robinson.

Ida Lock’s inquest began last month, more than five years after she died – the delay was down to several reasons, including its particular complexity.

What emerged was just how profoundly many of those lessons had not been learned. Particularly egregious, says Ms Robinson, was a suggestion from a midwife – shortly after the birth – that Ida’s poor condition was linked to her smoking, something Sarah had never done in her life.

“The amount of days I cried because I thought I’d done something wrong… every Christmas, every holiday, you always have this heavy weight that you shouldn’t be having fun. And all along, some people knew.”

Meanwhile, the staff who had delivered Ida were told in an email that “they had demonstrated excellent teamwork, and had all worked in the best interests of mum and baby”.

As the coroner found on Friday, Ida’s death was wholly avoidable, caused by a failure to recognise that she was in distress prior to her birth, and then a botched resuscitation attempt after she was born.

By the time she was transferred to a higher dependency unit, at the Royal Preston hospital, she had suffered a brain injury from which she could not recover.

Having failed to deliver their daughter safely, Ida’s parents would have expected that the trust would properly and openly investigate her death. Instead, they pursued an investigation that Carey Galbraith, the midwife who completed it, would later describe as “not worth the paper it was written on”.

They didn’t take responsibility for their failings despite having an independent report from the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB) – a body that examined questionable maternity care – clearly stating their shortcomings.

“Our efforts to get any answers have been met with a complete block,” said Ida’s father, Ryan Lock. “Particular people have told us to our face something that wasn’t the case, that Ida was poorly before she was born, and that’s the reason why that this happened.”

PA Media

PA MediaClearly, the Morecambe Bay report was not, as was hoped, a line in the sand for maternity services across England, or a rallying cry for widespread improvements. As the inquest has shown, it did not even lead to sustained improvement at Morecambe Bay.

Tabetha Darmon, chief nursing officer at the trust, said in a statement last week that it has made improvements since.

“We take the conclusions from the coroner very seriously and have made a number of the improvements identified during the inquest. We are carefully reviewing the learning identified to ensure that we do everything we can to prevent this from happening to another family.”

‘A woeful picture’ nationwide

Elsewhere around the country, other trusts have also been forced to face their failures, often by grieving families.

In March 2022, an investigation into services at the Shrewsbury and Telford NHS trust found that more than 200 mothers and babies could have survived with better care. Then, in October that year, a review into maternity services at East Kent Hospitals University NHS trust found that at least 45 babies might have survived if they had been given proper treatment.

And an ongoing review into the maternity care provided by Nottingham University Hospitals NHS trust, due to be completed next year, is set to be the biggest yet, with around 2,500 cases being examined.

Even that does not tell the full story. Families in several areas, including Sussex, Leeds and Oxford, want local investigations into their maternity services. And an annual review of units by inspectors the Care Quality Commission (CQC) paints a woeful picture.

In the commission’s latest report, published in September, not a single one of the 131 units inspected received the top rating, Outstanding, for providing safe care.

About a third (35%) were rated as Good for safety, around half (47%) were rated as Requires Improvement while almost a fifth (18%) were deemed Inadequate, the lowest grading.

“While we identified pockets of excellent practice,” wrote the CQC, “we are concerned that too many women and babies are not receiving the high-quality maternity care they deserve.”

Professor James Walker, who used to be the clinical director for HSIB, said that from his visits around England, the problem was that maternity units “didn’t have the skills, the finances, or the drive to actually make the changes that are required.”

Ida Lock’s inquest was a case in point. What emerged over the inquiry was that the midwife delivering Ida was not compliant with crucial training in heart-rate monitoring, that staff did not know how to investigate incidents or realise they should inform external regulators of an unexpected death.

“It’s deeply distressing,” says Dr Kirkup. “It’s bad enough that other trusts didn’t listen, but for it to happen again in this same trust is unforgivable.”

From poor culture to lack of teamwork

Listening to his exasperation brought me back to the autumn of 2022. On that bright morning, Dr Kirkup was speaking at the publication of his inquiry into maternity care in East Kent.

Many of the failures he’d found there – poor culture, lack of teamworking, not listening to families, a failure to investigate incidents or learn from them – were a repetition of what he’d uncovered at Morecambe Bay seven years earlier.

He struggled to hide his frustration that here he was again, forced once more to explain to families why they had been failed by a trust that did not know how to do the right thing.

PA Media

PA MediaLike Morecambe Bay, East Kent deteriorated even after his 2022 inquiry. Within months of the publication, inspectors became so concerned about its services that they considered closing maternity care at one of its hospitals, the William Harvey in Ashford.

The CQC found that staff were not carrying out basic tasks such as washing their hands in between patients, or wearing gloves and aprons when delivering care, and that they were leaving urine and bloodstains in toilets.

The inspection highlighted how little the East Kent review had changed things where it mattered, front-line in the wards.

As the report had said, “there are deep-seated and longstanding problems of organisational culture” in the trust’s maternity units, including “disgraceful behaviour and flawed teamworking that were previously left to fester”.

In October 2024, the board of East Kent Hospitals Trust said that it apologised unreservedly for the pain and loss, and for the failures of the board.

It said: “We are on a journey to fundamentally transform the way we work. Changing the culture of a large and complex organisation takes time and there is much work still to do, but we are determined to succeed so that we are providing the right standard of care and compassion.”

Derek Richford, whose grandson Harry had died in avoidable circumstances in 2017 at East Kent, is now working with the trust to improve maternity care and argues that it is an uphill struggle. “It’s been a devil of a job,” he claims, “to get people in the trust to simply read the report, even the summary.”

Should medics be punished?

The question asked by some families is why heads haven’t rolled. There is a widespread recognition in healthcare that punishing medics for individual clinical errors does not necessarily lead to safer outcomes.

It can in some cases promote a defensive culture, where people do not own up to their mistakes and lead to individuals being blamed rather than supported to improve.

The day after the Shrewsbury maternity report was published, the then-Health Secretary Sajid Javid said his department would “go after the people responsible.

“I want to make sure that we leave no stone unturned in finding the people that were responsible for this and making sure that they are held to account,” he added.

Three years later, there is no evidence of anybody being held to account.

The Department of Health says it is “unable to comment on individual staffing responsibility while an active police investigation is taking place”.

£1.15bn of maternity-related payouts

Even when major reviews into maternity care have led to families getting individual feedback and told they had been failed, any subsequent legal action leads to NHS Resolution, the health service’s insurance arm, requiring that the case is examined afresh. This can add further delays and costs to the process.

NHS Resolution said that inquiries “do not look at cases from a legal liability perspective. Failings by a clinician might amount to errors of judgement, but that is not necessarily sufficient to constitute negligence under the law”.

In 2023-24, NHS Resolution paid out £1.15bn for maternity-related deaths and injuries, 41% of its total payments, despite maternity care forming a much smaller proportion of a trust’s daily activities.

“NHS resolution is this anonymous body,” says Derek Richford, “that you can’t get a name of the person you want to speak to. You can’t get any accountability. And those people are the puppeteers for the people below who have to run around doing their will. It’s wrong.”

‘The time for inquiries is over’

There are now calls for the government to establish a national maternity inquiry, rather than relying on individual ones at different hospitals and trusts. More than 36,000 people have signed up to one such petition, led by two sets of bereaved parents; while campaign group Maternity Safety Alliance is making a similar call. So far, the Department of Health hasn’t committed to a national inquiry.

Both Dr Kirkup and Prof Walker argue that the time for inquiries is over.

“Another inquiry will find exactly the same things that we find at the moment,” said Prof Walker, “we know what the problems are.”

What is needed is a national plan to improve maternity care, argues Dr Kirkup. He says he has been working with the Department of Health on drawing up plans to improve teamworking and providing compassionate care.

Streeting has said he will “fix our maternity services”, including supporting trusts to make rapid improvements and training more midwives, but has not detailed how he intends to go about this. “I just wish that the Secretary of State would announce his intentions,” says Dr Kirkup.

Prof Walker also believes that a national programme of improvement and oversight should be launched, taking the learning from individual investigations and ensuring it is embedded across the system. For it to be truly effective, he argues, it will require a specific type of leadership.

“The NHS traditionally doesn’t appoint leaders,” he says, “it appoints managers, people who come in and take the status quo that’s there, and just make sure that it gets more efficient. That doesn’t make it better, or innovate or improve.

“One of my frustrations over the years, working in various places, is I kept being told ‘we don’t do that’. And I kept on saying, ‘why don’t we do that?’ The simple questions are always the best ones, because they challenge the status quo.”

Prof Walker highlights that there has been some progress in recent years, however. The latest figures on Maternity and Newborn Safety Investigations (the successor body to HSIB) show that the number of incidents of both potential and severe brain injuries have decreased.

Back in East Kent, Mr Richford has observed some changes too. “We have a new board of directors that appear to be doing the right thing – they’re certainly saying the right thing,” he says.

“[But] even now, seven years on [from Harry’s death], it’s still not as it should be. We are still trying to make sure that the trust is being as transparent as they say they are.”

As for Ida Lock’s parents, the road on which their daughter would have grown up leads directly to Morecambe Bay, and a small patch of sand. This is where they scattered some of her ashes. Now they refer to it as Ida’s beach. When they pass by, with their two other children, they regularly blow her a kiss across the sand.

Their fervent hope is that other couples do not experience a similar fate. But they know that long before them, other families also suffered – and they aren’t confident that more won’t in the future.

“Those families went through what we’re going through now,” says Sarah. “But nothing came of it. You can’t trust that [improvements] are ever going to happen.

“I hope something does change.”

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.