There’s an old saying among doctors: if you’ve seen one 80-year-old, you’ve seen one 80-year-old. Some will act like they’re 60 or 70, while others seem a lot older. So, instead of asking How old is too old?, shouldn’t the question be, How old is too old for what function?

“Absolutely. I could not agree more,” said Dr. Louise Aronson, a geriatrician and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Her bestselling book “Elderhood” is about redefining old age. “I honestly think anybody who’s lived past their 40s knows age matters,” she said. “Your body changes, your brain changes. What I would like to see is a conversation where we actually discuss the things that matter.”

Bloomsbury

But it get tricky, when you have wisdom brushing up against decreasing cognitive function.

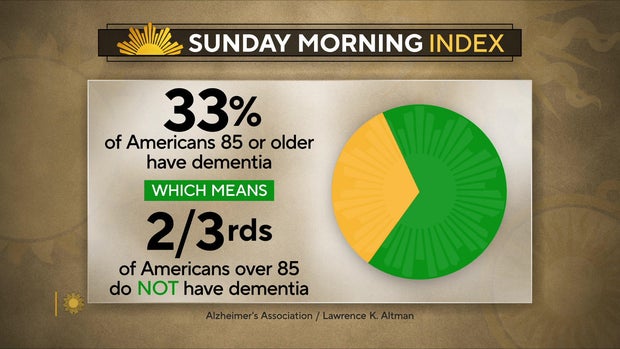

A healthy human brain has up to 100 billion nerve cells making trillions of connections with each other. Recent research suggests a normal part of aging involves forgetting less important memories to help make room for new ones. The problem comes when normal forgetting is coupled with an abnormal process causing dementia.

Dr. LaPook said, “I would say by far the biggest fear my patients have is that they’re losing it. And very often it’ll start with, ‘I couldn’t think of the name. I mean, it was somebody who I know so well.’ How important is that? How worried should they?”

“I would say they should not be worried,” Aronson replied.

And what about misplacing objects? “Sometimes it’s a matter of attention,” Aronson said. “So, what may be happening in situations where people said, ‘I couldn’t find my keys,’ is that they weren’t paying enough attention to the keys. Maybe they were talking to someone when they put them down and consequently that memory isn’t within their grasp in the way they would hope.”

But if they find the keys and don’t know what the keys do? “Oh, that’s a bigger problem!” Aronson said.

That distinction between normal and abnormal aging is increasingly important as the number of older workers continues to grow. In most cases, mandatory retirement at a certain age is illegal, but there are exceptions when public safety is at stake: for example, FBI agents must retire at 57, commercial airline pilots at 65.

But there are no age limits for surgeons.

Dr. Mark Katlic, a thoracic surgeon and chief of surgery for LifeBridge Health in Baltimore, said, “When I lecture about this subject of older surgeons around the country, I ask my audience who in the audience has encountered the surgeon who should have stopped operating before he or she did, and the majority of hands go up.”

In 2015, Katlic created the Aging Surgeon Program, a two-day physical and cognitive evaluation open to older surgeons from anywhere in the world. His multidisciplinary team of doctors – including geriatricians and neurologists, physical and occupational therapists, ethicists and lawyers – built a comprehensive, objective evaluation of the surgeon’s physical and cognitive faculty.

Asked what the initial response was of the surgeons who were going to be subjected to this, Katlic replied, “Almost everyone comes kicking and screaming and not wanting to come.”

And what precipitates them being sent there in the first place? “Something has been identified as being problematic,” Katlic said.

Aside from evaluating surgeons flagged with a possible problem, LifeBridge is one of the few hospital systems in the country where all doctors and nurses over the age of 75 receive a neurocognitive assessment every two years. Dr. Katlic, 72, says tests like these actually help fight ageism by focusing on function rather than on chronological age. He said, “I think you can make a very strong case for anybody who’s in a high-impact profession – doctors, airline pilots, high government officials – they should have some sort of screening at some age. In fact, I would take away the mandatory retirement for airline pilots and others. If you’re okay, the test will show you’re okay.”

Aronson said, “We’ve added a couple of decades, essentially an entire generation, onto our lives, and we haven’t kind of socio-culturally figured out how to handle that.”

Figuring out how to handle that, says Aronson, might just mean embracing the realities of getting older while realizing the end of working doesn’t have to mean the end of a meaningful life. “We need ways of letting people work when they still can, and of helping them to stop working when that’s in their interest and the interest of the common good,” she said.

LaPook said, “But the problem is that we really haven’t figured out a way of giving people a gentle off-ramp to whatever it is that they’re doing, that preserves their dignity and their sense of who they are?”

“Yeah, almost all of us will live to that phase of life,” Aronson said. “And so, if nothing but the most selfish of reasons, we should be doing that right now.”

For more info:

- Louise Aronson, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University

- “Elderhood: Redefining Aging, Transforming Medicine, Reimagining Life” by Louise Aronson (Bloomsbury), in Hardcover, Trade Paperback, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.org

- Mark Katlic, chief of surgery, LifeBridge Health Systems, Baltimore

- The Aging Surgeon Program

Story produced by Mark Hudspeth. Editor: Remington Korper.

CBS News

See also: