Johannesburg — Scientists in South Africa have claimed a discovery they believe could force us to rethink some fundamentals of what it means to be human.

Deep inside the Rising Star cave system, about 20 miles outside Johannesburg, a group of young scientists led by American paleoanthropologist Lee Berger claim to have found gravesites of small-brained hominids dating back between 236,000 and 335,000 years, much older than the first known human graves from a cave in Israel, which date to about 92,000 years ago.

Paleoarchaeologists have long assumed that larger brains eventually brought our later ancestors more complex thought, allowing for the development of complicated language, the control of fire and other advanced concepts — such as burying their dead. This discovery, Berger believes, will start to turn that conventional wisdom on its head.

Foto24/Getty

In 2013, Berger sent out a casting call for six “underground astronauts.” He was looking to build a team of archaeologists with caving backgrounds who could fit through the tiniest space — just 7.5 inches wide — to reach a possible hominin site.

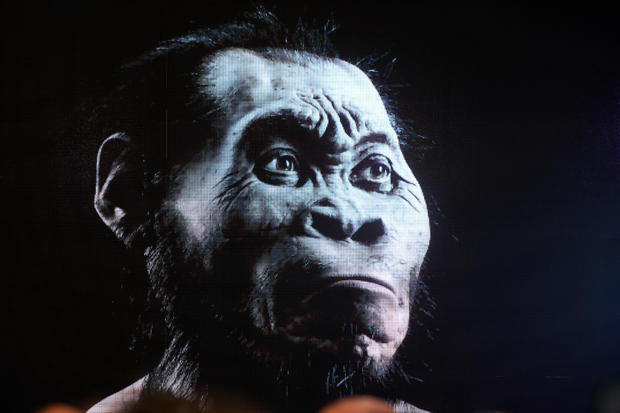

In 2015, the team announced the discovery of Homo naledi, a small-brained hominin species of which they had recovered some 1,500 fossils. Homo naledi was small, with a brain only about one-third the size of a human’s. They looked more like chimpanzees than modern people.

Humans are not believed to have evolved directly from the Homo naledi species — they were more like cousins than direct ancestors to homo sapiens.

Berger and his team continued to toil in the cave system, examining sediments, soil and rock for other clues on the new species. Late last year, they announced that the creatures were able to make fire and use it as a tool, based on charcoal and burn remnants they found in the cave.

On Monday, the team announced that homo naledi had used fire to light the way through the cave system to deliberately bury their dead, while marking their graves with artwork on the cave walls.

Berger described to CBS News some of the challenges and questions his team has grappled with over the years.

“It’s dark, it’s dangerous, it’s difficult. They’re (homo naledi) going hundreds of meters back in here, down chutes and into little spaces, and one of the great dilemmas has been, how? Were they just lost? Were the bodies in here because they got lost and can’t find their way out? But why only them, and why in these spaces?”

LUCA SOLA/AFP/Getty

Berger said these questions kept the team searching for more. They set up a miles-long system of cabling to rig up cameras and provide an intercom system, so he could speak with the cavers as they excavated in real time.

“Those images were so grainy” he said. “It looked like the first moon landing. Even though I was only 170 meters away from them, I couldn’t see anything, and it was so tough.”

Berger eventually put himself on a strict diet and lost 55 pounds to be able to go into the caves himself. He told CBS News it was the toughest challenge of his 30-year career. But once he sat down on a ledge deep underground, looked up and saw the telltale signs of fire all over the cave ceiling and walls, he said it was worth it.

“Nothing beats being there,” he said. “You do need to see it. There is a very human part of exploration.”

But with passages just inches wide to squeeze through, it’s a risky business. Berger got stuck on the way out for several hours. He said at one point, he believed he was going to die there.

LUCA SOLA/AFP/Getty

“It was the most horrible thing I’ve ever done in my life. And the best thing,” he said, admitting that he didn’t plan to go back down.

The team said a number of symbols had also been found on the cave walls, some of them hashtag-like signs which they believe may have been left to mark the graves.

In one of the graves, the scientists found what they described to CBS News as a tool-shaped rock.

Three academic papers on Berger’s team’s findings are currently under peer review and will eventually be released by the journal eLife. In the papers, the team outlines how layers of sediment are mixed in the areas around the bodies, indicating what they say is the digging and filling of individual graves.

They say they’ve discovered fossilized bones from at least 27 Homo naledi individuals of various ages, all of whom lived at least 240,000 years ago, and possibly as long as 500,000 years ago.

John Hawks/Wits University

Berger said he expected his team to be accused of rushing to publish their research before a peer review was completed. He argued that, in the age of modern technology and social media, it was worth making all their findings available immediately, to be built upon by the scientists of tomorrow.

He said his team also expected their discoveries from the Rising Star caves to challenge some of the most important aspects of what we think makes us human.

If the small-brain Homo naledi were capable of complex thought, that might “give us pause to think about how we as humans have placed ourselves on a pedestal,” Berger told CBS News. “If you open up any of your dictionaries — Webster, Oxford, Google — and type ‘what makes us human?’ It will say, ‘having the characteristics of people.’ How arrogant is that?”

“There’s no definition of us,” Berger said. “I think discoveries like this are going to begin to force us to actually define what it means to be human.”