Mewshaw opens by recounting his lifelong admiration for — call it obsession with — Greene, whose works he first encountered in high school. Summarizing Greene’s posh background (inherited wealth, Oxford classmates such as Evelyn Waugh), Mewshaw contrasts it with his own harsh upbringing in a Washington-Baltimore “blue-collar suburb.” But what most absorbs him is locating their similarities — mainly their Catholicism. Watching “The Power and the Glory” adapted for television “stunned me … its discussion of Catholic dogma embedded in … the propulsive momentum of a thriller.” Touchingly, young Mewshaw hopes that if the story’s “whisky priest could be redeemed,” so could his divorced parents and stepfather.

Alas: Mewshaw’s youth reads like a train wreck. Everyone drinks; a neighboring murderer’s brother moves in — whom Mewshaw’s bipolar mother either “smothered with affection or slapped his face beet red.” Mewshaw also gets into physical battles constantly: “at that time … a masculine rite of passage.”

Yet from his adolescence, Greene remained a sort of North Star whose writing career, Mewshaw hopes, “might be a template for mine.” So, he hopes, might Greene’s way of life: When Greene writes “My roots are in rootlessness,” Mewshaw identifies. Greene roams the world, braving political and mortal perils. Mewshaw hitchhikes across the country and later signs on as a deckhand for a doomed skipjack off the Chesapeake Bay. Rather than “be transported back [from Vietnam] in a body bag,” Mewshaw applies to graduate school — and is accepted.

This terrifies him. He flees to the Caribbean, narrowly escapes death there and returns to the United States to be directed by a priest to a psychiatrist.

Mewshaw’s surge of details never flags, by turns bold and lurid. He marries, becomes a teacher, receives a Fulbright grant to write in Paris, submits a novel to Random House for publication, and manages to install himself and his wife, Linda, in an area “half an hour” from where Greene had taken up residence in Antibes.

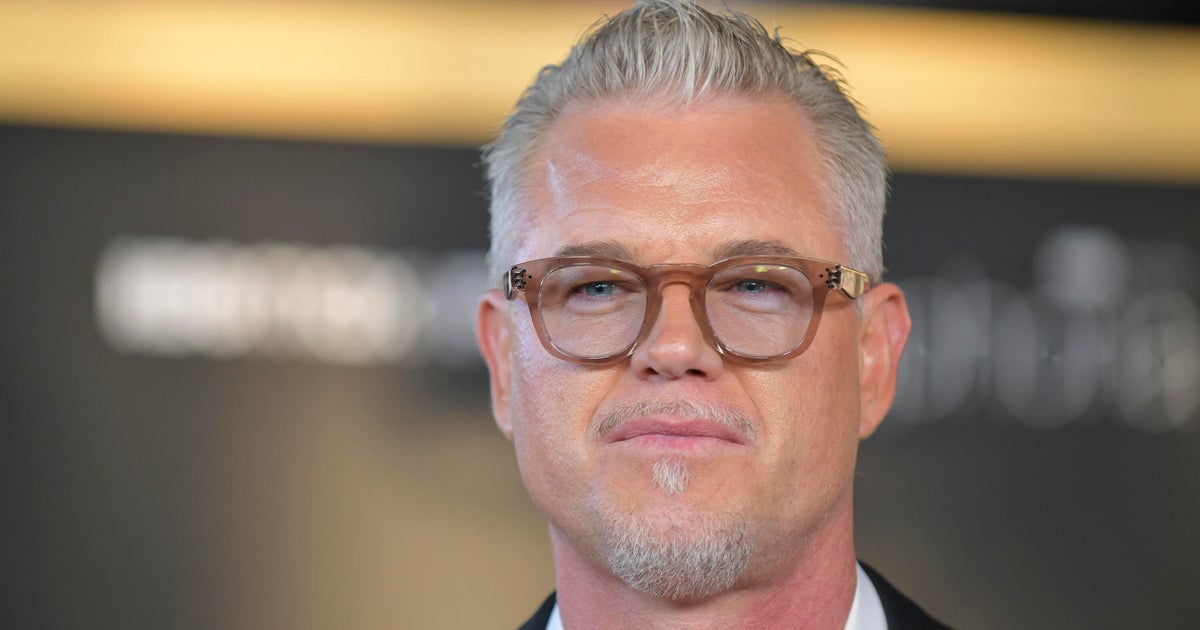

At this moment we finally reach the title’s promised meeting. Although Greene blows off an introductory letter, as Mewshaw tells it, Mewshaw tries again — and “to my astonishment, Greene replied, inviting Linda and me to his apartment for drinks.” Mewshaw and Linda find themselves confronting “a very old man, fragile, stoop-shouldered, with oysterish blue eyes that avoided mine,” whose face had elsewhere been called “hurt, offended … metaphorically bruised by events.” Fame dogged him: “For the rest of his life … Greene answered [the phone] by barking, ‘Who is this?’”

Such particulars are irresistible, and “My Man” teems with them. Haltingly, a friendship develops — amid complicated travel, family-rearing, illnesses and (never least) books published. At notable intervals the men eat, drink and encourage each other’s work.

Relations snarl, however, when Mewshaw produces a 1975 profile of Greene (printed in full in “My Man”) that’s picked up by the Nation, then plagiarized by Penelope Gilliatt in the New Yorker. When Greene finally reads the piece, he explodes at Mewshaw by letter: “I don’t think any journalist has done worse for me.” The two then trade long, impassioned (epistolary) arguments — also reproduced in this book’s pages.

Suddenly, Greene snaps: “Let’s forget all about it.” The friendship staggers on — enmeshed with extraordinary events, places, names — through Greene’s failing health and poignant end, in 1991.

I confess it’s hard to read “My Man” without feeling that Mewshaw has something to prove. What in fact emerges from this dishy, sometimes showy, often tragicomic chronicle is Mewshaw’s overpowering drive to advance a writing career, and (no surprise) Greene’s inscrutably conflicted, shape-shifting relationship to — well, everything. The ride’s like something out of Boccaccio: strange, wild and memorable.

Joan Frank’s latest books are “Late Work: A Literary Autobiography of Love, Loss, and What I Was Reading” and “Juniper Street: A Novel.”

Getting to Know Graham Greene

A note to our readers

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program,

an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking

to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.